GNUstep is an open-source implementation of the Cocoa development environment that runs on a variety of *nix systems as well as on Windows. In the past weeks I’ve been working on a build pipeline for virtualised GNUstep dev environments, and here’s why.

In which the author goes on rambling about why virtualisation is useful

Virtualisation is an incredibly useful tool for many IT organisations. It enables you to streamline system deployments, isolate applications from one another or even move them into the ever so lofty ‘cloud’. So if you are a professional developer or ops person, it’s clear why you might care about virtualisation technologies. Even outside that purview people easily recognise the benefits of, e.g., running a virtualised Windows system alongside your Mac OS or Linux desktop for that one pesky Windows application you can’t get rid of.

You also have a pretty good reason to look at virtualisation if you are working on an open source project and want to decrease the barrier of entry for potential contributors: Downloading and running a virtual machine image is an order of magnitude easier than wading through 20+ steps of installation instructions that might or might not work for your particular machine.

The sad state of Objective-C packages in Debian

The only thing arguably more convenient than a virtual machine is if your native package

manager provides packages for you. So if you wanted to get started writing Objective-C

applications on a Debian derived Linux distribution, you’d just type

apt-get install gnustep-devel and start coding. Right? Well yes and no. You

could start writing Objective-C that way, but if you’ve had any prolonged

exposure to the language on the Mac OS X or iOS platforms in recent years,

chances are that you’re about to give yourself a stroke:

- You just wrote

@propertyin the interface definition and expected your getters and setters to be synthesized? Oops, the compiler will only let you do it the old way (explicit@synthesize). - You want to weakly reference your delegate object? Think again, that’s not supported.

- You’ve become accustomed to thinking about object ownership instead of memory

allocations because automated reference counting keeps track of that for you? Better

flex those muscles needed for writing your

-deallocmethods: Manual reference counting is all the rage. - Just chuck some work onto a background queue using

dispatch_async()? Nope. Neither clang as a compiler with blocks support, nor libdispatch are GNUstep dependencies, and worse yet, the version of libdispatch that ships with Debian won’t even work with Objective-C blocks in GNUstep.

The depressing thing about this situation is that you can actually use all these modern features on a GNUstep based Objective-C stack, but you’re not only left to your own devices in order to do that, the package manager actively gets in your way:

You want to build the GNUstep runtime library instead of the one that ships with GCC (that one is effectively unmaintained since 2011). To do that, you will install clang using apt-get. But unfortunately the clang package in Debian depends on the GCC runtime, so if you go that route, you’ll alway have to make sure that you don’t accidentally link the wrong runtime.

Alternative ways to get a GNUstep environment

There are a few alternative ways to get a GNUstep environment that alleviates at least some of these problems:

- Philippe Roussel provides a package repository with packages for Debian 7/Ubuntu 14.04. It doesn’t have libdispatch, though.

- Ivan Vučica has published a build script, which also doesn’t build libdispatch.

- The Étoilé project has installation instructions that provide a nice starting point (including libdispatch).

All these are perfectly valid, commendable approaches, and I generally think that for end-users we absolutely want proper packages, but as a developer, I think you already get a lot of benefits from having something that

- provides a modern Objective-C environment

- is ideally installable with no more than two or three commands

- does not mess up the environment it is being installed into (and can be removed without residue)

Turnkey GNUstep development environments using Packer and Vagrant

The upshot of this – and the justification of my aimless pontificating about virtualisation – is that for someone coming from Objective-C development on an Apple platform a virtual machine with all the needed tools would be an excellent starting point, at least for the ‘let’s see how much of my iOS code compiles on Linux’ variety of projects.

My approach to this has been to automate things as much as possible and make the resulting images available in a convenient way. Firstly, I decided that the method of distribution should be primarily using Vagrant, which allows you to abstract from the concrete virtual machine monitor you are going to use (VirtualBox, VMware Fusion, etc.) and provides ways to easily (and reproducibly) provision VMs (Vagrant calls them ‘boxes’) for different projects.

The way theses boxes are being build is using Packer. Packer essentially is a build pipeline for Vagrant boxes and other deployment artefacts (Docker containers, AMI images) Using Packer, I was able to build Vagrant boxes for VirtualBox and VMware Fusion/Workstation as well as Docker containers. The battle plan is as follows:

- Install the base OS (Debian 8)

- Configure vagrant specific integration points (user, ssh keys, guest file systems) if necessary

- Install ansible

- Run an ansible playbook to install:

- clang (compiler)

- libobjc2 (Objective-C/Blocks runtime)

- libdispatch (work scheduling)

- gnustep-make (build system)

- gnustep-base (Foundation)

- gnustep-gui (AppKit)

- gnustep-back (drawing and event handling backend for gnustep-gui. Think CoreGraphics, but without an external API)

- Gorm (Interface Builder)

- Remove any unnecessary stuff (including ansible)

It took a while to iron out the kinks, but in the end it worked surprisingly well. So well actually that it’s easy for me to just rebuild all the artefacts on a weekly basis. It takes a couple of hours (most of the time is spent building clang though, and I intended to stop doing that once Debian drops the dependency on the GCC runtime).

Installation is deceptively easy:

vagrant init ngrewe/gnustep-gui

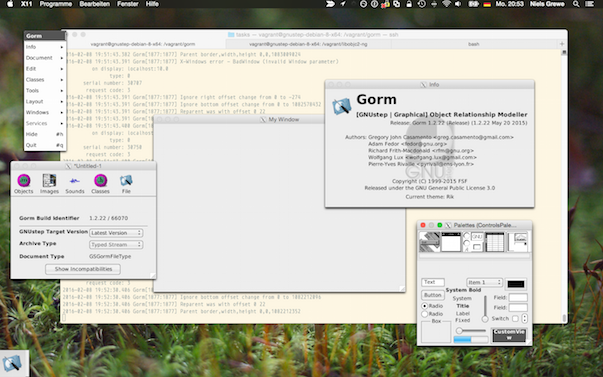

vagrant upAnd it will give you the ability to build and run GNUstep applications inside the VM. If you have a X server on the host machine, you can even export the GNUstep equivalent of the Xcode Interface Builder to your machine:

vagrant ssh -- -Y Gorm

Note: GNUstep actually supports NIBs, so there’s the possibility of porting over some of your interface files as well.

Apart form that there’s no IDE provided in the environment. There is

ProjectCenter, which provides a

few IDE features, but you’re usually much better of

writing makefiles

yourself. The good thing is that using Vagrant you can do that using your familiar

editor on the host machine and only run the make commands within the VM.

Decisions Made

Build clang from source

This decision might be considered a bit non-obvious, since Debian already provides a clang package. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, this package also depends on the GCC Objective-C runtime, and I’ve seen to many situations where people ended up linking the wrong runtime version, so it’s better to ignore the packaged version until this can be resolved.

Building clang from source also allows access to some of the newer Objective-C features (generics come to mind), which aren’t supported in the packaged version yet.

Enable the full non-fragile ABI in gnustep-base

The non-fragile ABI is a wonderful thing. Using it, adding or removing ivars

no longer breaks binary compatibility. To take full advantage of this, the

base library is compiled using the --diabled-mixed-abi switch, which means

that no instance variables are exposed in the headers.

Use the ‘cool’ sorting algorithm

This is a bit of a dogfooding exercise: Quite some time back, I implemented support for (compile-time) pluggable sorting algorithms in the gnustep-base (Foundation) library. One of the reasons for that was that different parts of the codebase were actually using different algorithms (quicksort and shellsort) and it made a lot of sense to unify that. But the pièce de résistance of that work was the implementation of the timsort algorithm, which is also used by Python and the JDK and has really nice performance characteristics for real-world inputs. Unfortunately, I have yet to convince people to use it as the default algorithm, so I’ve taken the liberty of doing that in my build pipeline, if only to increase the chance that it get’s a bit of testing under its belt.

Isolate gdomap

gnustep-base comes with a name service for its native IPC mechanism (distributed objects). It’s called gdomap and usually needs to be installed setuid root or even run as root itself. In the vagrant boxes, I’ve moved it away from its default (priviledged) port and made it run as a separate user. I’ve also written a systemd unit to control the daemon instead of relying on GNUstep applications starting it themselves at random times.

Install a theme

The built-in look of GNUstep is very reminiscent of NeXTStep, and it’s quite often the subject of intense debate on the GNUstep mailing lists. My impression is that most casual users judge it to be too heavy duty, industrial, or utilitarian. Fortunately, GNUstep is fully themable, so the boxes come with the Rik theme, which provides a much ligher look.

Lessons Learned

I’ve also learned a couple of things in the process that are independent of the concrete project but still worth sharing:

Always be able to provision using a Vagrantfile

The first major stepping stone is that building a VM using Packer is slow, relatively speaking. Even if you have cached all the iso images and packages locally, it still takes quite a while to get even past the initial installation stage of the OS. It’s much more convenient to try out the changes in your provisioning script directly from a Vagrantfile and only trigger a Packer build when you are confident that it won’t error out in the middle of provisioning. Also, using tags liberally in ansible helps a lot to cut down build times if you are just trying a new piece of functionality.

Embrace the OS standard way of doing things

Carefully installed environment variables go a long way, especially with

GNUstep, which uses a large number of environment variables to specify the

the locations of bundles, frameworks and such. But things are really much neater

if you stick to the way Debian usually handles these things. So instead of doing

export CC=clang all the time, simply use update-alternatives to install it

as the system default compiler. Yes. That works even if you built it manually.

Yes. There is an

ansible module for

doing so as well. For everything else, you can simply stick shell script

fragments in /etc/profile.d to ensure that whenever you get a shell, you get

the correct environment without sourcing anything.

Beware of indirections between Docker and Packer

I’m building the images on an Mac OS X host, which means that the Docker daemon runs in a virtual machine itself (through boot2docker). That extra layer of indirection creates problems:

- You need to place the TMPDIR in a location shared between the host and the docker VM, so that docker has access to the build scripts etc.

- If you have your build directory in a non-standard location (outside /Users), you might need to mount it manually in the docker VM.

This is not really a big deal (plus it’s the result of running in a bit of an idiosyncratic build environment), but you need to be aware of it.

If weird things seem to happen: Don’t trust the Docker builder’s output

I can’t find the Packer issue documenting this anymore, it I ran into a problem

along the way where my Docker builds would just error out at a random point,

without any indication why and exit codes that didn’t seem to be correlated with

whatever it was doing: The explanation was that sometimes the stdout/stderr

streams from the container can lag behind a bit and you are not seeing the

thing that caused it to break. So if you run into inexplicable problems, a few

strategically placed sleep statements might shed some light on what’s going on.

Wrap-up

Packer, Docker, and Vagrant are all excellent tools to facilitate building predictable development toolchains and the availability of such toolchains might help attract contributors to a project. The GNUstep environments succeed in providing a Objective-C programming environment that provides a set of language features that is comparable to that on Mac OS X and iOS.

The Vagrant boxes and Docker images are available through the default channels of these tools, more concrete installation instructions and the build scripts can be found on on GitHub